No place like home

by Isobel Whitelegg

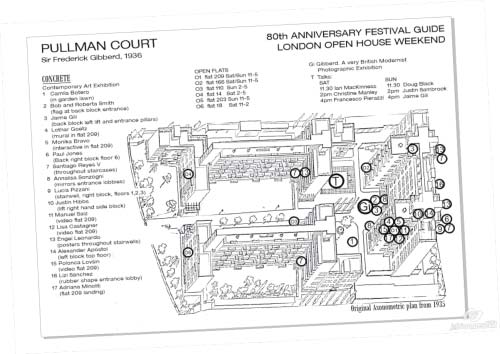

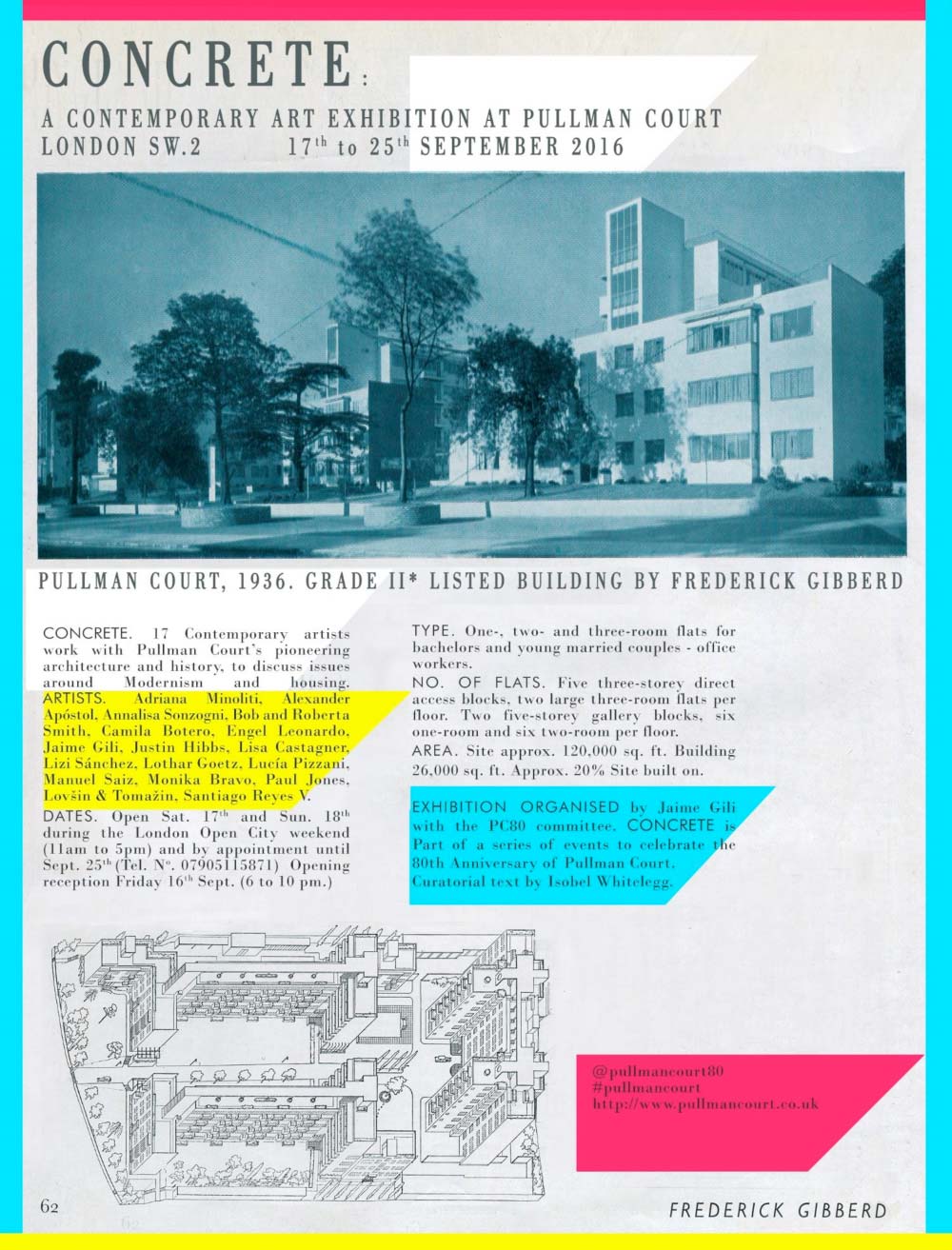

The history of modernist architecture (and its residential projects especially) is often linked to the word utopia, a “no-place” that belongs to fiction and has no foothold in reality. Not all modernist architects however were primarily concerned with immediately projecting their designs into the realm of total social change. Frederick Gibberd's Pullman Court (1936) was a modest proposal, a privately funded and relatively low-density scheme intended for single professionals and smaller families. His approach to its design, informed by his sustained consideration of the model of the modern flat in its various possibilities and permutations, was practical. He invested considerable care in the details that would affect daily life of the people who live here. Bespoke built-in furniture would maximise space, glass-paned hallway doors would increase natural light. This care also extended to his aesthetic choices, the placement of a pillar, the colours the walls were painted. This is not utopian, it is just care invested in a place through the work of design.

Seventeen artists have placed works within and amongst Pullman Court's buildings and grounds as part of Concrete. Many of these draw attention away from the grandiose idea of utopia and back to the small details that made this a place one designed to be functional but also as somewhere people might enjoy living. Jaime Gili's intervention, for example, acts as a form of aesthetic repair, undoing later alterations in order to restore a formal integrity to Gibberd's plans. The notion of Pullman Court as a practical thing designed with care also finds a concise form in a work by Santiago Reyes, whose photographs depict various placements of a basic tool ( a wedge that might be used as a doorstop) that is crafted from purpleheart wood, a material as strong as it is exquisite.

Gibberd's interest in the modern flat was an argument for a certain way of living, made at a time when there was a need to construct better housing for London's inhabitants. His two bêtes noires were the “small-house speculator” and the “professional landlady,” each of whom he perceived to be in the business of dictating how people live in the interest of personal profit rather than responsible design. Gibberd proposed the construction of flats with shared green spaces (and with access to a view, fresh air and communal services) as an alternative to the suburban house with its own garden, gate and garage. Rather than spinning former city dwellers further outwards, the more centrally located modern flat could economise space and also save the leisure time otherwise lost to a workday commute. The time of Pullman Court's construction however coincided with the wide-spread building of many more homes of a different style - small houses produced by a new generation of construction companies, and marketed under names that truly do seem utopian, such as Costain's 'Arcadia Wonder House' (1936).

Whereas Pullman Court was designed for rent, the construction and occupation of new suburban houses was supported by increased access to mortgages, as well as the accelerating use of advertising as a means to market home ownership (“why rent?” became a strap-line). The individually managed house might been sold under the maxim that an Englishman's house is his castle but Gibberd viewed sole responsibility for utilities and upkeep as merely an “expensive encumbrance” and a waste of individual energy. By the standards of now, Pullman Court's original shared facilities seem more like privileges than services. In its day, the development included not only a social club, restaurant and dedicated doctor's surgery, but also a communal swimming pool, here brought back to life through a work by Polonca Lovsin.

Polanca Lovsin, Swimming Pool Again, London, 2005, video still

Published a year after Pullman Court's completion, Gibberd's book 'The Modern Flat' was a compilation of research into housing models in Europe and the Americas, citing privately-funded projects as well as successful state-subsided schemes, such as the then very recently completed Kensal House (Committee of Architects, 1937) in London's Ladbrook Grove. Before the post-war reconstruction of the 1950s however, the majority of affordable London housing remained wedded to an architectural vernacular that was low in height and traditional in appearance. Pullman Court's international style modernism therefore stands out in London in a way that it might not in other cities where modernist housing achieved a denser presence. It finds the greater proportion of its peers in other places. Within Concrete, Gibberd's discovery of a parallel but more developed modernism in Venezuela is emphasised in works by Lucia Pizzani and Alexander Apostol.

Being inside Pullman Court's grounds therefore feels less like being here, and more like being in another city. It feels like an exceptional space, and this is a sense that is exaggerated by the reasons you might be visiting it now: viewing it as a architectural-museum-of-itself as part of Open House or as a site for a series of temporary artistic interventions as Concrete. Visiting this place and seeing it as something other than its day-to-day existence, as a place where people do live, does not make it a utopia. This experience however brings it closer to the type of spaces Foucault described as heterotopias - which included museums and festivals amongst other spaces subverted from the norm by the play of the imagination. One of Foucault’s core examples of a heterotopia is that of the mirror, a space in which we see ourselves being somewhere other than where we know ourselves to physically be, and one whose disorienting relation to the real is subtly exploited here in the work of Annalisa Sonzogni.

Annalisa Sonzogni, Pullman Court, Installation view, London, 2016

What seems more important to remember now however is that Pullman Court is a real place, and one that still works well for those that inhabit it. Aside from the endurance of his architecture, still standing (minus its swimming pool) 80 years later, Gibberd's arguments also remain relevant. London's housing is in crisis, a situation that is driven by the pernicious present-day equivalents of both the professional landlady and the speculative builder. The definition of what is affordable has been inflated to a level beyond the reach of so many of those who need to live here. If we argue that housing should be thought of as anything other than a mere market we are called utopian. The architects best celebrated seem not to be not those solving the problem of how we live, but instead are the authors of monumental signature buildings. Gibberd's modest proposal (celebrated here under a flag by artist Bob & Roberta Smith bearing the words of political theorist Hannah Arendt 'Performance, Participation, Association') might encourage us to keep on arguing otherwise.